Case Study

Getty Research Institute: The Digital Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex was created between 1575 and 1577 under the guidance of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish Fransiscan friar, who led a group of Nahuatl scribes and artists over three years. Work on the codex was completed within the walls of the Imperial College of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco whilst shielding from the Great Pestilence of 1576.

Destined to be sent to the King of Spain, the aim was to create an encyclopaedia of Nahua knowledge and customs of central Mexico, which prior to the Spanish Invasion, had been part of the Aztec Empire, to support the conversion of the native population to Christianity.

The codex was written in Nahuatl and Spanish and is richly illustrated, and the parallel texts and images form three distinct narratives. As a result, with its rich encyclopaedic content about pre-Hispanic and early colonial Mexico, it is for Mesoamerican scholars one, if not the, most important manuscript. The codex travelled to Europe and was acquired by the Medici family and now is housed in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

Fast forward approximately 450 years, and coincidentally during the more recent pandemic, a joint team from Digirati and the Getty Research Institute (GRI), who commissioned this project, collaborated on the development of an enhanced digital version of the codex. This time with the aim of unlocking the content, making the text and images searchable and providing a rich digital interface that will meet the needs of all potential users from school children to specialist academic researchers.

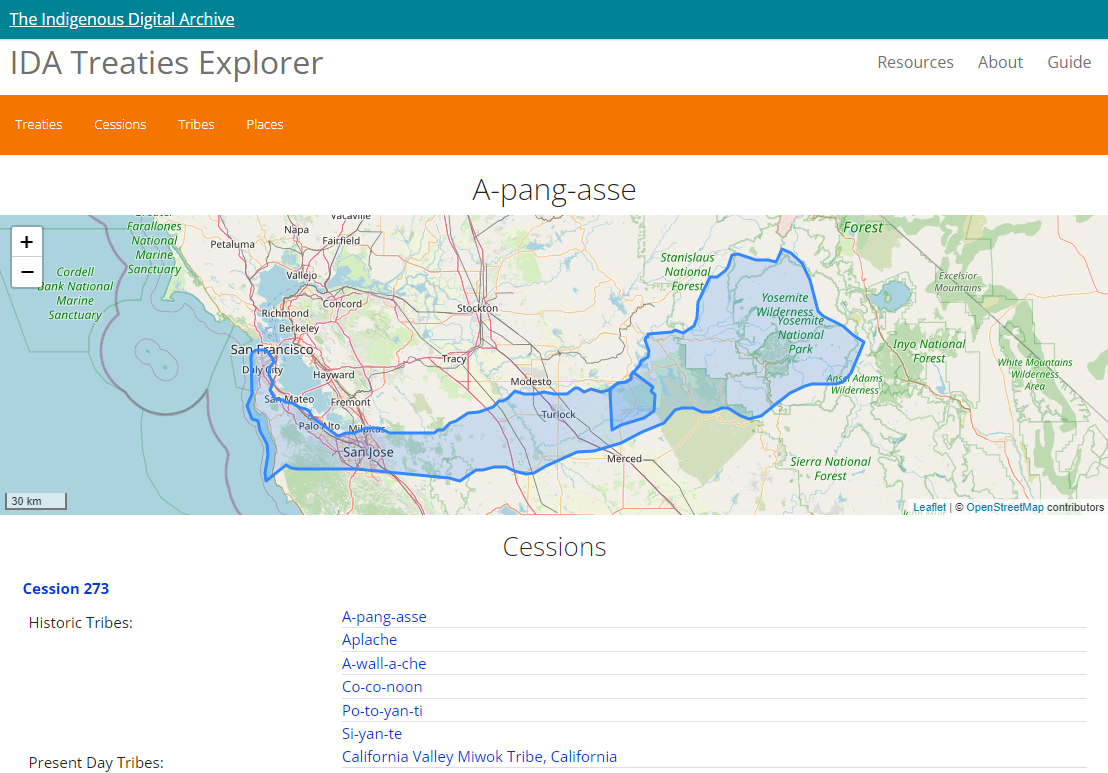

The Digital Florentine Codex (DFC) is a digital critical edition which brings together the many disparate supporting resources such as transcriptions, translations, essays, and other materials necessary for studying the manuscript. This is facilitated by a configurable ‘three narratives’ multi-column view in which a digitised manuscript page can be viewed alongside multiple translations and transcriptions of both the Spanish and Nahuatl texts.

The ‘three narratives view’ design concept to bring together required supporting material for a given folio.

The ‘three narratives view’ design concept to bring together required supporting material for a given folio.

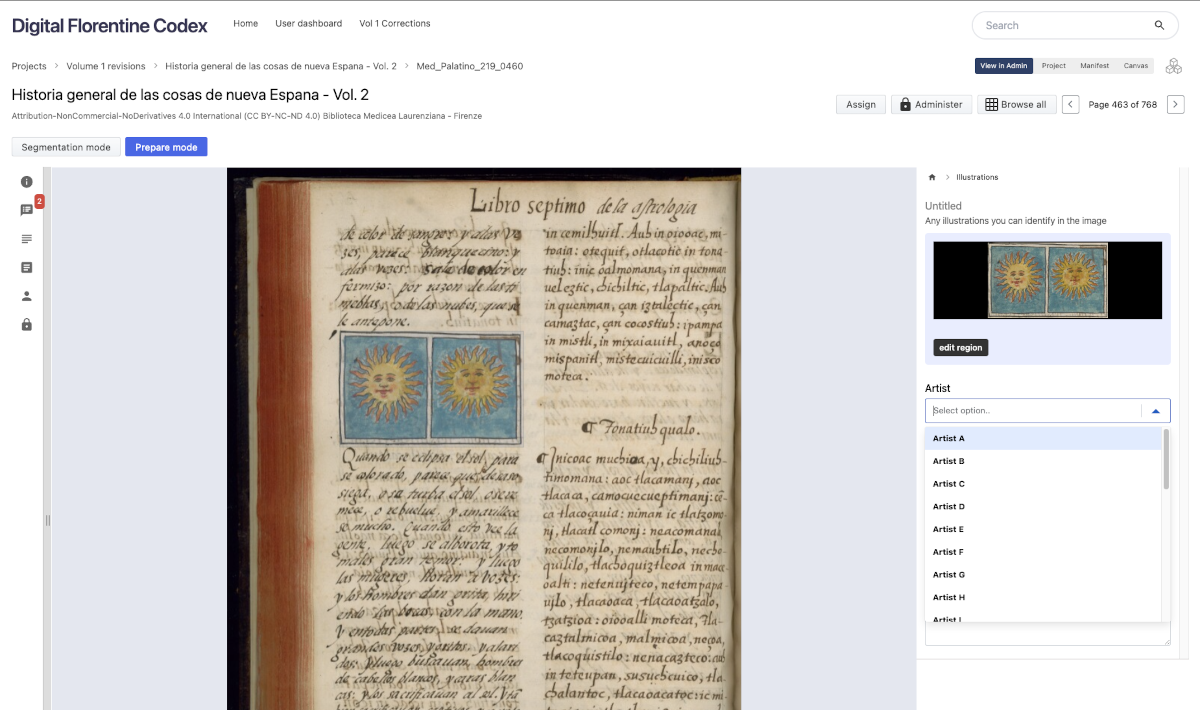

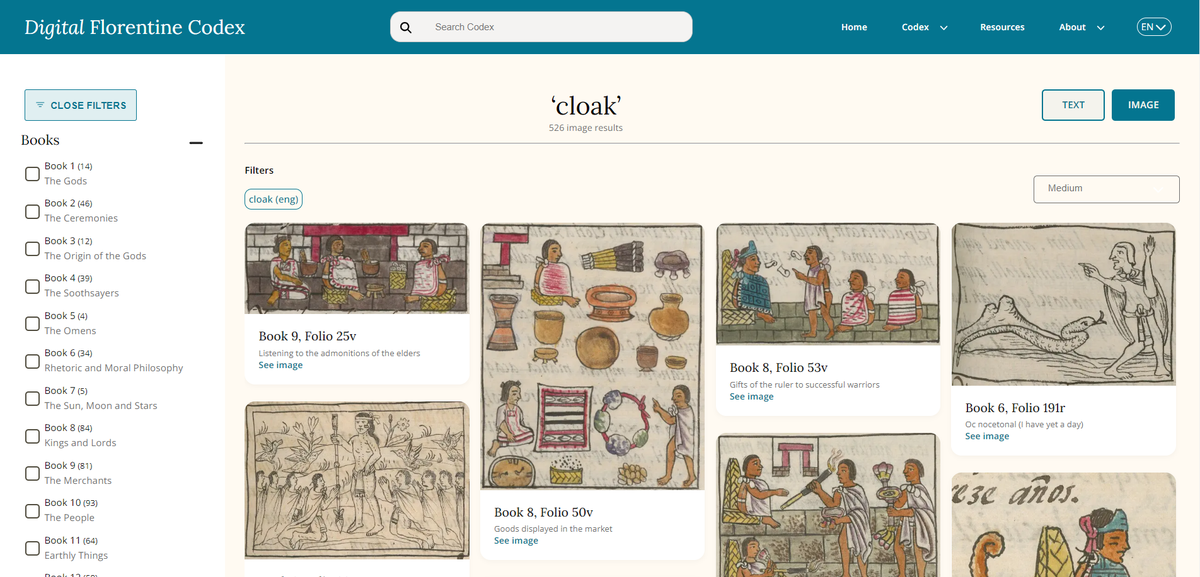

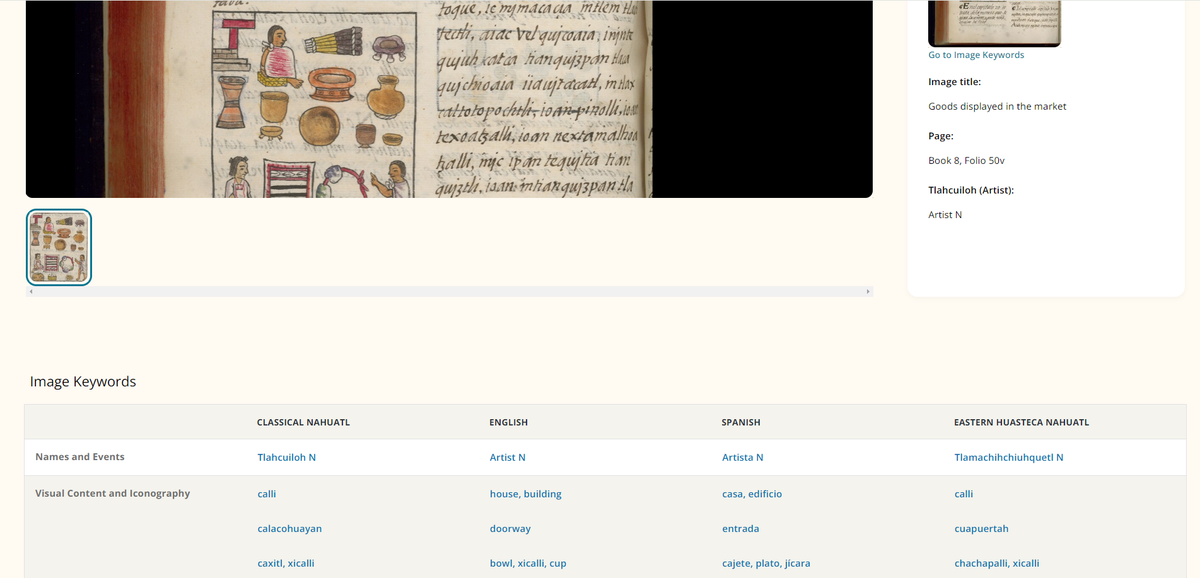

Another important aim of this project is to help revitalise the Nahuatl language, which is considered endangered, by creating a bridge from 16th-century Nahuatl to modern Nahuatl speakers, providing translations and audio recordings. All texts—translations and transcriptions—were incorporated into a powerful index to enable them to be easily searched. In addition, the images within the manuscript were tagged with rich iconographic tags taken from the Getty Vocabularies and provided in English, Spanish, Classical Nahuatl and modern Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl, enabling users to explore the images within the codex by theme and content.

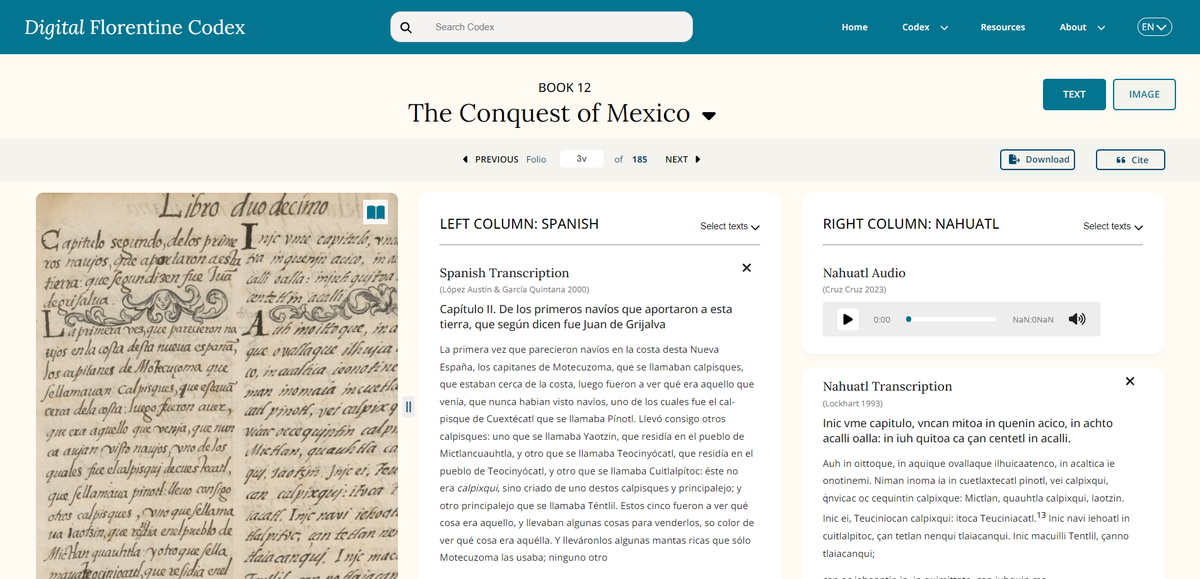

This tagging process was assisted by Digirati’s crowdsourcing and annotation tool Madoc which was used to create bounding boxes for images which could be associated with multiple images tags and was used to tag an image or section of text with a specific scribe or artist (although their names are not always know they are identified by stylistic idiosyncrasies). In this way, users can explore the content within the codex by creator, as well as by content. As with the Getty Vocabulary tags, these tags were also provided as search facets so that users could filter by a specific scribe or artist, which enables users to get an overview of their work across the manuscript. Users can combine tags so that, for example, it is possible to find all images by a particular artist which concern a particular topic or theme.

Identifying images and artists using Madoc

Identifying images and artists using Madoc

With nearly 2,500 pages, thousands of tags, and eight or more transcriptions or translations per page, the tagging, translation, and vocabulary work that was completed represents a significant effort for GRI and their partners. As a flagship digital critical edition, the Digital Florentine Codex brings together scholarly material created by specialist researchers including art historians, experts in Mesoamerican languages, historians of the period, native Nahuatl speakers, and many others into a single, easily navigable rich interface which allows expert and non-expert users alike to explore the full breadth of the content contained within the codex.

Metadata-driven image search

Metadata-driven image search

Viewing terms associated with an image

Viewing terms associated with an image

Digirati led the design process (based on Design Thinking) for the DFC, with collaboration with GRI, and then delivered the technical implementation. The design process built on user research already commissioned by GRI, synthesising the identified user needs into a set of design concepts and a content model that reflects the content needs of users and the relationships between content elements. Together these outputs informed the data model for the large amount of data produced, and the overall user experience of the website which was based on the paradigm of Generous Interfaces.

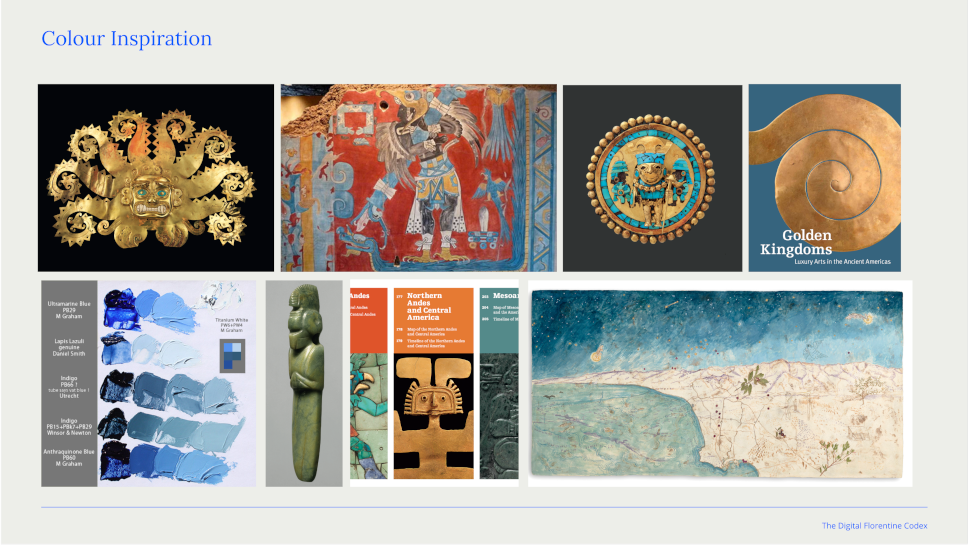

A visual design was then created with colours and typography inspired by the codex and other artefacts and materials from Mesoamerica.

Some of the materials considered for visual design inspiration.

Some of the materials considered for visual design inspiration.

The site was built using the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) standard which aligned very neatly with the data model required for the DFC. This means that the content and metadata can easily be reused outside of the confines of the site with other IIIF based tools, but also it was possible to utilise other IIIF-based tools and components for the build of the site. In addition to Madoc one such component was Canvas Panel, a re-usable component that enabled us to make the user interface of the DFC much richer in the time available than would otherwise be feasible. Canvas Panel was also funded by Getty, and developed by Digirati in parallel to this project, and has been adopted more widely by software developers specialising in user interfaces for Cultural Heritage material.

Here is a short video (5m) walkthrough of the DFC by key members of the GRi delivery team: Senior Research Specialist Kim Richter and Senior Project Manager Alicia Houtrow. This was delivered as part of a presentation at the original online launch event in 2023. Since launch the site has had over 75,000 active users globally, with 2.4 million page views and an average session duration of 10 mins. It’s been adopted in school and university curricula, cited in academic research, and praised by Indigenous scholars for its accessibility. It received a Bronze Medal at the Anthem Awards (2025) for its impact in education and culture, and was shortlisted for the Apollo Awards Digital Innovation of the Year (2024).

The DFC is available here: